By Laura Thornton

Meeting Tashamere, you’d never guess she’s been admitted to the hospital more than two dozen times. At 13, she’s a lively, vivacious teenager who loves gymnastics and modern dance and has the biggest smile.

But every year or two, she gets an MRI scan done of her brain, and once a month, she misses half a day of school to receive a vital blood transfusion. Her mom, Inetta, takes her to The Johns Hopkins Hospital, where she’s transfused with about two to three units of blood.

Tashamere has sickle cell disease, an inherited blood disorder that, untreated, can cause crises of intense pain and lead to stroke. She also has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which can frequently co-occur with sickle cell disease, explains Dr. Eboni Lance, Tashamere’s neurologist and medical director of Kennedy Krieger Institute’s interdisciplinary Sickle Cell Neurodevelopmental Clinic.

Before 2012, when Inetta became Tashamere’s foster mom, Tashamere didn’t always get the treatment she required. But she’s flourished under Inetta’s love and care. Her blood transfusions keep her from experiencing a stroke or pain crisis, and regular appointments with Dr. Lance ensure she gets the neurological attention she needs. “Tashamere is receiving all the treatments necessary to protect her body and brain,” Dr. Lance says, “and she’s thriving.”

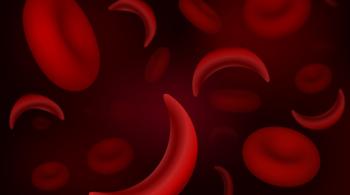

When Cells Sickle

With sickle cell disease, the body’s hemoglobin—the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen throughout the body—is stiff and sticky, and doesn’t carry oxygen well. When red blood cells lose oxygen, they contract into a sickle shape that, combined with hemoglobin’s stickiness, can make the cells clump up and block blood vessels, potentially causing a pain crisis, explains Dr. James F. Casella, Johns Hopkins’ chief of pediatric hematology and Tashamere’s hematologist since she was 3 months old.

Sickled cells can also lead to a silent cerebral infarct—not a stroke, but a possible precursor to one. An MRI scan can reveal whether someone has already had a silent cerebral infarct. “That means we can screen to prevent a stroke,” Dr. Casella says, “instead of waiting for a stroke to happen.”

A routine newborn blood test led to Tashamere’s sickle cell diagnosis. When Tashamere was 4, an MRI scan indicated she had experienced a silent cerebral infarct at some point in her life. A subsequent screening test—a transcranial Doppler, or TCD, which measures blood flow in the brain—showed that her risk of stroke was very high: greater than that of the average patient with sickle cell disease. Dr. Casella, who runs a weekly hematology clinic at Johns Hopkins, started her on blood transfusions to reduce that risk.

At the end of every transfusion, only about 30 percent of Tashamere’s blood cells are sickle-shaped. “At that point, the transfusion is very effective at reducing the likelihood of stroke—that’s the power of these transfusions,” says Dr. Casella.

How Neurology Can Help

It’s not uncommon for people with sickle cell disease to also have neurological conditions like ADHD, seizures, learning disabilities, behavioral or developmental complications, and executive or cognitive dysfunction. The Institute’s Sickle Cell Neurodevelopmental Clinic, which Dr. Lance established in 2014, is one of only a few clinics in the world offering comprehensive neurological and neuropsychological testing, behavioral evaluations, and follow-up recommendations for patients with the disease. Dr. Lance is leading two research studies that, she hopes, will help better explain the connection between sickle cell disease and the neurological conditions that so often accompany it.

When Tashamere was 7, Inetta mentioned to Dr. Casella that Tashamere’s behavior was often disruptive. Dr. Casella referred Tashamere to Dr. Lance for evaluation, and since then, Dr. Lance has worked with Dr. Casella to oversee Tashamere’s medical and mental health care.

At every appointment, Dr. Lance screens Tashamere for any medical or mental health conditions, checks up on how she’s doing, and makes sure her medications for ADHD aren’t interfering with her treatment for sickle cell disease. Occasionally, Dr. Lance recommends adjustments in medication type and dosage to Tashamere’s psychiatrist. A few years ago, she provided documentation to ensure Tashamere would receive the accommodations she needed to shine at school.

If Dr. Lance ever notices any changes in Tashamere’s behavior or development, she’ll recommend another MRI scan of her brain, and she’ll review the scan with Dr. Casella. Should the scan indicate any changes in Tashamere’s brain health, they’ll work together to adjust her treatment plan.

A Good Prognosis

Drs. Lance and Casella say Tashamere has a good prognosis. “She’s been able to come off a lot of the medications she’s been taking,” Dr. Lance says, “and she’s doing really well in school.”

Thanks to the care Tashamere receives from her doctors and family members, she’s in good health and gets good grades—almost all A’s and B’s. She’s in seventh grade, and her studies include business, Spanish and pre-algebra. “She says science is her best subject,” says Inetta, who adopted Tashamere in 2016, “and that she wants to be a lawyer when she grows up.”

At one point during a recent appointment with Dr. Lance, Tashamere’s face broke into a big smile, as she and Dr. Lance shared a private joke. Inetta couldn’t help smiling too, thinking: “She’s loved, she’s getting the best care, and I really think she’s going to be just fine.”

Watch Dr. Lance describe what sickle cell disease is and how clinic staff members collaborate to create individualized treatment plans for each patient.

For more information about sickle cell treatment at Kennedy Krierger, visit the Sickle Cell Neurodevelopmental Clinic page.