By Laura Thornton

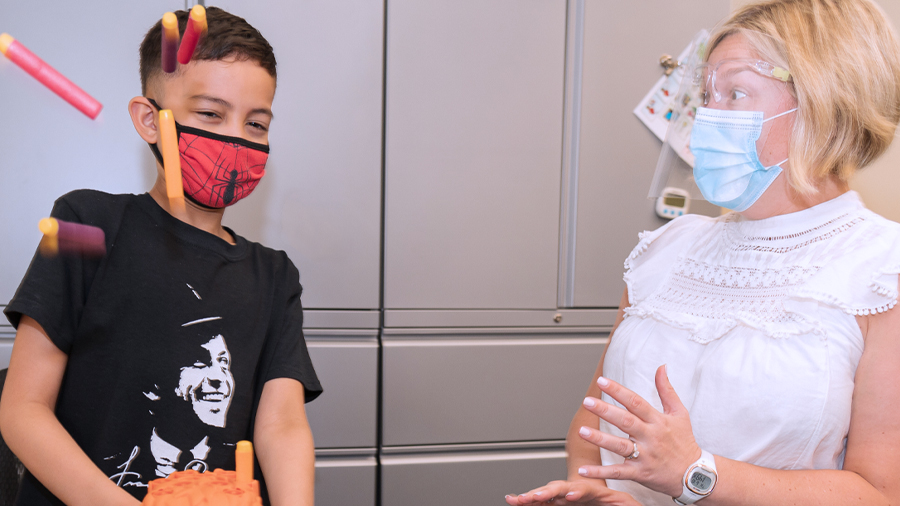

Creed and speech-language pathologist Christine Feinour.

Michelle will never forget the day she and her husband finally found the best school for their son Creed.

It was in 2016, and they’d already visited several schools for students with special needs, but none had felt just right for Creed, now 12, who has autism spectrum disorder. The last school on the list was Kennedy Krieger Institute’s Fairmount Campus school, in downtown Baltimore. It was a little far from their home near Annapolis, but wanting to be thorough, they made an appointment to take a tour.

“Walking into the school was like taking a breath of fresh air,” Michelle recalls. “It had classrooms, a gym, a library—all the things you’d hope your kid would be able to have access to.”

School staff members led Michelle and her husband through specially designed therapy and sensory rooms. “They showed us how they’d meet all of his needs, and talked about how they’d help him in different situations, while still making us feel really comfortable about all of those things,” Michelle says.

When the tour ended, my husband and I looked at each other and said, ‘Wow, this is it!’ There were no other considerations. This was the environment we wanted for our son. There was so much joy and happiness there—we just knew it was the right place for Creed.”

– Michelle

Better and Better

Kennedy Krieger’s special education schools serve students whose learning needs cannot be met by public schools. The Fairmount Campus serves students in prekindergarten through grade eight. The Institute’s Greenspring Campus in northwestern Baltimore is home to Kennedy Krieger High School, serving students in grade nine through age 21, and the LEAP (Lifeskills and Education for Students with Autism and other Pervasive Behavioral Challenges) Program, for students ages 5 through 21 with complex academic, communication, social and behavioral needs. In Maryland’s Prince George’s County, the Institute’s Powder Mill Campus serves students in grade two through age 21.

When Creed was 6, he and his family moved from Hawaii to the mainland U.S. to give Creed greater access to medical and educational services. Creed attended public school through the second grade, then his teachers recommended nonpublic special education.

“Since Creed started at Kennedy Krieger, we’ve seen him change in so many ways,” Michelle says. “He’s gone from not really knowing how to interact with another student or verbalize when he needs help, to being able to play with other kids, and have a dialogue with us in his own fun, creative way. Every year, he just gets better and better.”

“Creed is really energetic, very positive and outgoing,” says behavioral specialist Robert Falloni, who’s worked with Creed for several years. Lunchtime can be hard for Creed, as he has some food aversions, so he often spends that time with Falloni—and a little karaoke machine. They sing—Creed loves Frank Sinatra songs—and enjoy lunch together. Falloni also works with Creed throughout the school day, helping Creed when he gets frustrated with his schoolwork. And Creed receives mental health services to further help him cope with his frustrations.

“Initially, Creed had trouble asking for help, and if he was stuck, he’d get upset,” says Falloni, who developed a checklist of things—deep breathing, sitting quietly—Creed could do to calm down. Falloni would talk Creed through his frustrations then transition him back to his schoolwork. “Now, if he needs help, he’ll say, ‘I need help.’ And if another student is having a tough time, he’ll tell the student, ‘It’s OK.’”

‘I Can Do It!’

Creed recently completed the sixth grade. During much of the past year, he attended school virtually, to adhere to pandemic-related social distancing protocols. “He rocked the virtual classroom,” Falloni says. “He knew the schedule, he knew the routine, and he’d be in the [virtual] waiting room when it was time for class.”

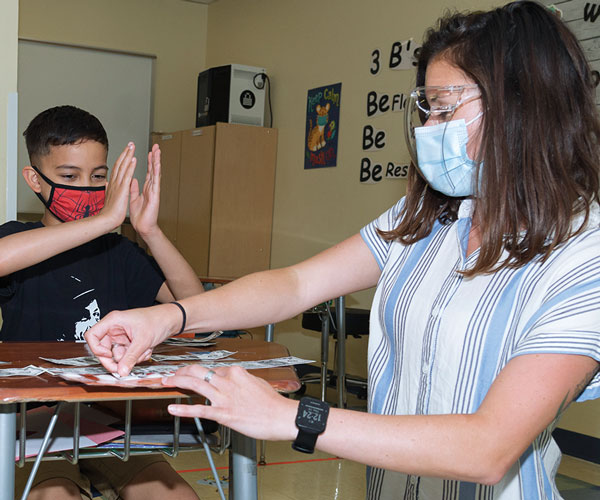

On his first day back in the classroom, “He came right in and was so happy and ready to be here,” says his teacher, Chelsey Bush. During one activity, “Someone else answered a question, and Creed turned around and said, ‘Well done!’”

Bush and assistant teacher Hannah Baron model positive thinking for their students. Baron sometimes pairs affirmation statements with yoga. “We’ll do the tree pose, and Creed will say his affirmation,” she explains. One day last spring, Baron was helping Creed with a math problem. “Before I could prompt him, he said, ‘I’m smart; I can do it!’” Baron says. “It was a breakthrough moment.”

“It’s really neat to watch Creed’s progress, from saying a couple of words and phrases here and there, to now having so much to say,” adds speech-language pathologist Christine Feinour, who’s worked with Creed for the past few years on speech, social skills, interacting with peers and problem-solving. “When I think of Creed, I think of this bright, creative student who brings so much joy to all of his teachers, peers and family.”

Creed’s parents are so glad they made that trip, four years ago, to visit Kennedy Krieger. “We want our son to be as independent as possible, and to be able to make friends and be confident and kind to others,” Michelle says. “I know that everyone at Kennedy Krieger is trying to help Creed learn, little by little, so he can grow and mature, and say, ‘I can do this, I understand that, I believe in myself.’ The more he can say that, the more he can be the best human he can be in this world.”