By Laura Thornton

With every electrode they place on someone’s head, the research team at Kennedy Krieger Institute’s Research Neurophysiology Laboratory is one step closer to learning more about how electrical activity in the brain affects things like motor control, inhibition and nonverbal communication.

That’s a lot of information to be gleaned—but also a lot of electrodes.

The team works with children and teens who’ve chosen to participate in clinical studies at Kennedy Krieger. Some participants are neurotypical, while others have brain-based diagnoses such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Most participants get an electroencephalogram, also known as an EEG—a painless, harmless, noninvasive test that measures electrical activity in the brain, both at rest and while doing things like tapping fingers or imitating gestures.

Ultimately, we hope to be able to use these biomarkers to complement psychology testing…to get a fuller picture of a person’s brain.” – Dr. Joshua Ewen

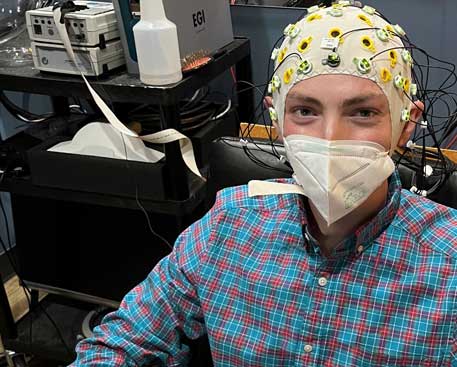

During the EEG, each participant wears a snug-fitting cap with dozens of electrodes affixed to it. The electrodes “listen” to and record the electrical activity in the brain, allowing the lab’s researchers a detailed glimpse at the brain’s inner workings.

“We’re looking for biomarkers in the brain that indicate how each person’s brain functions,” explains Dr. Joshua Ewen, the lab’s director. “Ultimately, we hope to be able to use these biomarkers to complement psychology testing—or even to get information that psychological tests aren’t able to deliver—to get a fuller picture of a person’s brain, as well as to track their response to brain-based therapies.”

“We’re merging psychology and neuroscience,” adds Michael Levine, a former member of the lab’s research team.

In particular, the team is studying motor control in children and teens with ASD or ADHD. Those with ASD may have difficulty imitating other people’s gestures, affecting their ability to communicate nonverbally, while those with ADHD might have difficulty with inhibition—restraining certain movements while making other movements. The team also studies neurotypical kids and teens as part of a control group.

A Helping Hand

In addition to this work, the lab’s research team also helps other researchers—across Kennedy Krieger and The Johns Hopkins University—use the lab’s EEG equipment. That means prepping the lab, training outside researchers to use the equipment, helping them design their EEG experiments, and assisting with data analysis and interpretation, explains research team member and biomedical engineer Evan Bucklin.

“We’re also looking at new ways to analyze the data—new techniques that can focus on specific questions that might not have been asked before,” says Bucklin, who is analyzing new automated tools for processing EEG data.“If, with strong proof, the biomarkers we’re looking for were ever to enter clinical practice, then these automated tools will greatly help people around the world,” Dr. Ewen adds.

But to get to that point, Dr. Ewen and his team need time—and participants. “We want to answer as many questions about the brain as we can, as rigorously as we can, and as quickly as we can, and we can only do that if we have high levels of recruitment,” he says. “If someone had a magic wand and asked us what we needed to do that, the answer would probably be: ‘Research participants.’”