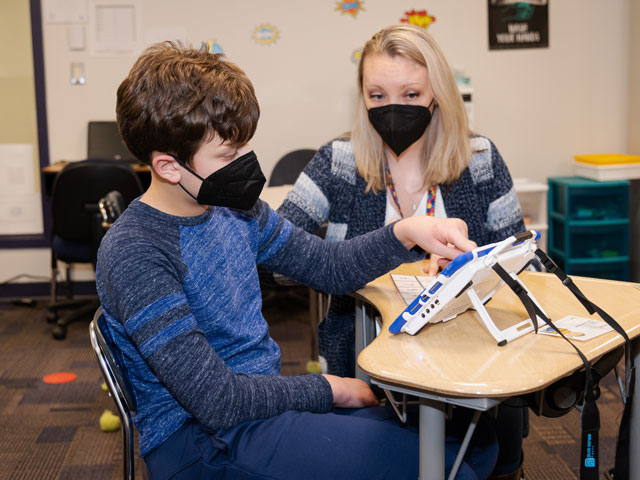

Jack, a student and patient at Kennedy Krieger, uses an AAC device to communicate with his teacher, Jessica Berry.

By Laura Thornton

Think about the last time you asked someone a question. Maybe you asked if they wanted to meet for lunch, or where the nearest gas station is. Imagine trying to ask that question without speaking.

For individuals who are nonspeaking, have unclear speech or use minimal speech, communication can be difficult. Writing can be cumbersome for those with motor difficulties, and nonverbal forms of communication—gesturing, facial expressions, body language—aren’t always precise. That’s where augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) can help.

Some forms of AAC—including pointing and looking at people, things, words and pictures—use no technology at all. Other forms use the latest communication technologies: apps for smartphones, iPads, and tablet and personal computers, and separate AAC devices designed specifically to help people communicate.

“AAC devices and apps are tools that improve daily communication for someone who is unable to communicate fully using natural methods,” explains speech-language pathologist Lauren Tooley, who manages the Institute’s Assistive Technology Clinic. “Using an AAC device or app allows someone to communicate whatever they want, when they want. They can request, comment, reject—it allows for all kinds of different intentions.”

Using AAC allows someone to communicate whatever they want, when they want.” – Lauren Tooley

Evaluation Is Necessary

AAC devices and apps run the gamut, from simple to complex. Some use pictures or icons, with the user selecting a picture or icon of what they want the AAC device or app to say aloud for them. Other devices and apps use words, or a combination of words, pictures and icons. Many also include common phrases, such as “How are you?” and “I need a break.”

An evaluation with a speech-language pathologist is necessary to determine which form of AAC is best for someone who is nonspeaking or minimally speaking.

At Kennedy Krieger’s Assistive Technology Clinic, speech-language pathologists work with individuals who are nonspeaking or minimally speaking—and often with their families as well—to match each individual’s communication needs and motor abilities with the right form of AAC for them. For example, individuals with motor difficulties may find touching buttons on a screen too arduous or time-consuming, but may benefit from an eye gaze-tracking device, which tracks where their eyes look on a screen, and says aloud whatever word, phrase, picture or icon they’re looking at.

Once an AAC device or app has been selected, the speech-language pathologist will work with the individual and their family to preprogram additional useful words or phrases in the device. A football fan may want “Touchdown!” added to their device. Chess players will want “Checkmate!” to be among their phrases.

“Our assistive technology clinicians customize the device and figure out what vocabulary the child needs, including how much vocabulary makes sense for them right now,” explains Dr. Katheryn Boada, Kennedy Krieger’s director of speech-language pathology and assistive technology.

AAC devices and apps use various strategies for displaying words, pictures and icons on a screen, often in different categories, to take advantage of users’ strengths in language, organization and picture discrimination skills. Speech-language pathologists determine the best format for each user.

Once someone is fluent in using their AAC device, “It’s pretty amazing,” Tooley says. “Now that they have control over their communication, they can tell people what they want and how they feel.” Their behavior and interaction style may even change, as they get used to knowing what it’s like to be able to direct their daily needs and engage in spontaneous conversation.

“Sometimes, family members can get a little teary-eyed,” she adds, “especially when their child uses the device to say ‘I love you!’ for the first time.”