By Kristina Rolfes

On the outskirts of Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, you can hear the laughter and voices of schoolchildren bubbling through the open windows. One child, 7-year-old Sariyya, is quiet. Though no sound leaves her lips, she is communicating with her teacher. In front of her, on the tray of her wheelchair, lies a book of pictures. Sariyya’s gaze shifts from her teacher to the book before her, and back to her teacher. The teacher looks at the image of the cup in the book, and asks, “Sariyya, are you thirsty?” Sariyya’s gaze moves to the word “yes.”

It is a simple, yet ingenious eye-gaze communication system designed specifically for Sariyya by a speech-language pathologist at Kennedy Krieger Institute. The family traveled halfway around the world the previous summer to seek help with their daughter’s speech, eating, growth, and overall development.

Sariyya was born with multiple disabilities into a society that does not fully include or accept individuals with disabilities. No school in the area had the resources or expertise to meet her special needs. So her parents, Rizwana and Abdus, started the ALC Foundation in Bangladesh and opened a school of their own so that Sariyya and other children with developmental disabilities could learn. Thanks to the dedication of her parents and the team at Kennedy Krieger who gave her the means to communicate, the world of education and opportunity has opened for Sariyya.

Communication Without Boundaries

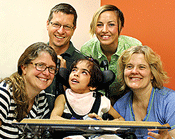

The family had been to many doctors and therapists over the years, unable to find a center that could meet all of Sariyya’s needs. Their family doctor recommended Kennedy Krieger Institute. The Institute’s international office coordinated the multiple evaluations, therapies, and follow-up appointments Sariyya would need during her visit to the United States.

Speech-language pathologist Mary Boyle assessed Sariyya’s speech and communication skills. She determined that Sariyya was very smart and could understand language, but she lacked the motor control and coordination to talk, use sign language, point to pictures, or activate switches. But what she could do, Boyle determined, was communicate through eye gaze.

Boyle developed a portable, picture book communication system, with boards arranged by topic for personal (getting dressed, pain, feelings, family members), social (favorite activities), and academic (letters, vocabulary words, etc.). Boyle taught her how to gaze, first at the person she was communicating with, then at a specific category or picture on her board. For the first time in her life, she could communicate. Sariyya said “I love you” to her parents for the first time with her new system.

“When a child can say, ‘I need this’ or ‘I hurt,’ and it is recognized, that is a major quality of life improvement,” says Boyle. “This is why I do what I do. We were able to provide Sariyya’s family a means to know their child better, and that is a gift I treasure.”

“Never had anyone communicated with Sariyya so warmly,” said Rizwana, Sariyya’s mother. “She loved that warmness, and we loved the way she was treated.” Unlike in her home country, people in Baltimore welcomed Sariyya wherever she went, she recalls.

Freedom to Play

Because of her motor impairment, Sariyya had never been able to play with toys as other children could. Children learn motor and social skills through play, so she had been missing out on important developmental opportunities. Occupational therapist Kristin Stubbs worked with Sariyya by modifying toys and working on play skills. Sariyya loves fairies, so Stubbs made a toy fairy for her that she could strap to her hand.

Sariyya’s parents were very worried about her growth and nutrition. Her mother had to spend an inordinate amount of time feeding her, because Sariyya lacked the motor skills to chew and swallow. Occupational therapist Donna Reigstad made recommendations, including showing Sariyya’s parents feeding techniques, using a special cup and spoon, and thickening liquids to keep them from falling out of Sariyya’s mouth. Ultimately, specialists in the Feeding Disorders Unit recommended a supplemental gastronomy tube, which delivers nutrition directly to the stomach, thus improving Sariyya’s strength and freeing up her time for more play and learning.

Assistive technology specialist Lauren Tooley provided a voice-output system using a computerized eye-gaze system, which she could use in addition to her picture book gaze system. The laptop-like device is equipped with a special built-in camera and sophisticated software that tracks where Sariyya is looking on the screen. By looking at particular words or pictures, she can generate speech.

On Sariyya’s last day at the Institute, the many specialists who worked with her during her visit gathered around and asked if there was anything else she needed. Sariyya shifted her gaze from the team to her eye-gaze system, which spoke her one last request before departing:

“Can I have a hug?”