By Laura Thornton

A few weeks into his stay at Kennedy Krieger Institute’s inpatient rehabilitation hospital, Ethan pondered his future.

It was the summer of 2020, he was slated to start his senior year of high school soon, and in about six months, he’d turn 18. If he wanted to become an Eagle Scout—a longtime dream of his—he’d need to complete an Eagle Scout project before his 18th birthday.

Earlier that summer, he’d experienced a hemorrhagic stroke caused by the rupture of an arteriovenous malformation (AVM), an unusual tangle of arteries and veins in his brain. He’d had the AVM all his life, but it had gone undetected until the rupture. An ambulance rushed him to a hospital near his home in Virginia, where he underwent brain surgery and clinicians worked around the clock to keep him alive.

Once he’d stabilized, he went to Kennedy Krieger Institute’s inpatient hospital for two months of rehabilitation. He had significant weakness on the left side of his body, and struggled initially to walk and use his left arm and hand. But the many hours of rehabilitation therapy he did each day soon started to pay off.

He also found the activities offered by the Institute’s Child Life and Therapeutic Recreation Department to be particularly helpful. The department’s specialists ensured Ethan had plenty of activities to do that were suited to older teens and which would help in his rehabilitation.

Card games had always been a favorite activity for Ethan, but in the weeks following his stroke, he wasn’t able to hold the cards in his hands. So he used a wooden card holder to hold his cards for him. Bonus: With the card holder, no one else could see his cards. “The card holder let me play games with my therapists and family, rather than just watch others play,” he says.

Ethan and his dad had an idea: What if Ethan could organize a project in which he and his fellow Boy Scouts could make a few dozen card holders and donate them to the department? It would be a wonderful way to give back and help others, and as a service project, would qualify him to obtain the rank of Eagle Scout.

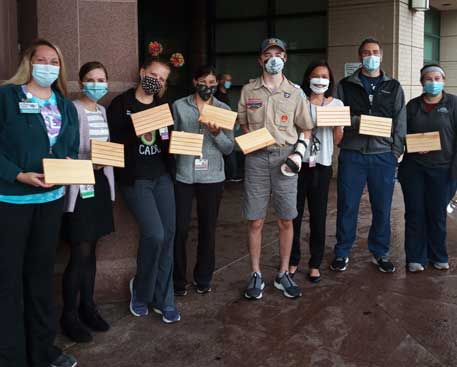

Ethan delivers the card holders to Kennedy Krieger.

‘He Just Took the Experience and Turned It Around’

Ethan progressed from using a wheelchair, to using a walker, to kicking a soccer ball around with his therapists. “He was incredibly motivated to get better,” says neuropsychologist Dr. Megan Kramer. “We taught him strategies to help him attend to his left side, and he incorporated them into his therapies. He was very engaged, asking questions to learn more about his condition. And his family was dedicated to helping him recover and were by his side, cheering him on.”

Ethan also started planning for the card holder project, sharing his ideas with Brittany Welsch, his therapeutic recreation specialist, who also became his sponsor for the Eagle Scout project.

“I helped him gather the information he’d need to get credit for the project,” she explains. “Part of my job is to help patients be ready to reintegrate into their community, and this paired nicely with helping him with the Eagle Scout project. I want my patients to be thinking about life after discharge, and that’s exactly what he was doing.”

Speech-language pathologist Kristy Chao helped Ethan organize and develop the plan for the project. While the stroke didn’t affect Ethan’s speech, it did impact his executive functioning. Organizing the project’s plan helped Ethan redevelop those skills again. Speech-language pathologists often help patients with skills like organization and prioritization, and these sessions were key to Ethan’s cognitive recovery.

Ethan was also thinking about school—he wanted to graduate on time. The school year started while he was still in the hospital, and classes were held virtually, due to the pandemic. In mid-September of 2020, he was discharged from Kennedy Krieger’s hospital, then underwent a second brain surgery. In mid-October of that year, soon after recovering from surgery, Ethan started as a patient of the Institute’s Specialized Transition Program (STP), a neurorehabilitation day hospital, doing several hours of therapy a day. In the late afternoons and evenings, he’d watch pre-recorded lectures and do his homework.

Because of pandemic-era restrictions on how many people could be at STP in person at one time, Ethan was on-site at STP for three days a week, and did virtual therapies from home on the other two weekdays. Virtual therapies also gave Ethan a little more time to do his schoolwork, as traveling to and from Kennedy Krieger was about a five-hour round-trip.

At STP, Ethan worked with educational specialist Ali Adler and speech-language pathologist Lynnley Moore on strategies to regain his organization skills, and to advocate for himself when in need of additional assistance. Adler also worked with him and his teachers on developing and implementing an individualized education program (IEP). Neuropsychologist Dr. Danielle Ploetz evaluated Ethan’s thinking skills and wrote a report for him to share with his teachers that included accommodations to help maximize his learning potential. Ethan’s hard work paid off, and he graduated in the spring of 2021. He’s now in college, and considering business school and possibly a future in real estate.

“Ethan worked really hard his senior year,” Adler says. “I just found him incredible. He was so resilient and diligent, and dedicated to his studies, despite all the challenges.” Moore adds, “He worked hard and applied the strategies quickly. He just took the experience and turned it around.”

Ethan also continued his physical and occupational therapies at STP. He worked his way back to being able to jog again, and then run, says physical therapist Erin Naber, who remembers watching Ethan show his dad the soccer skills he’d regained. “That’s the kind of moment you enjoy as a physical therapist, seeing patients and families enjoy the gains they’ve been able to make,” she says.

For occupational therapy, Ethan enjoyed using video games specially designed to improve hand movement, explains occupational therapist Nicole Andrejow. In virtual sessions, Andrejow helped Ethan with everyday activities. Once, Ethan made pizza with his family while Andrejow cued him on different organizational strategies (e.g., prepping the ingredients) and when to use his left hand. “He was so motivated by having his whole family in his environment,” she says. “Everyone was laughing, and he was working so hard.”

“I’m so grateful for all that Kennedy Krieger did to help me. It felt really good to be able to give back.” – Ethan

As a competitive video gamer, Ethan was determined to find a way to get back to the gaming level he’d been playing at before the stroke. After a few months of searching, he found a company that specializes in making custom controllers. Ethan now plays with a custom one-handed controller equipped with a joystick that he operates with his right foot.

‘A Positive Out of Something Very Challenging’

These experiences helped Ethan learn resilience at a young age. He never gave up on himself, or on the idea of giving back.

Shortly before his 18th birthday, after he’d finished at STP, he led a dozen of his fellow Boy Scouts in making card holders for the Institute’s Child Life and Therapeutic Recreation Department. When he returned to Kennedy Krieger to deliver the card holders, Welsch was so happy to see how much he’d progressed.

The card holders are used by the department on a daily basis. “They normalize adaptive play without bringing attention to it, and they’ll hold up for years,” Welsch says. “It was so great to see how Ethan was able to personally give back after overcoming his injury. He made a positive out of something very challenging. A card holder is so simple, but it can really help someone reintegrate back into the community, and Ethan has helped so many kids be able to do just that.”

“I’m so grateful for all that Kennedy Krieger did to help me,” Ethan says. “It felt really good to be able to give back.”