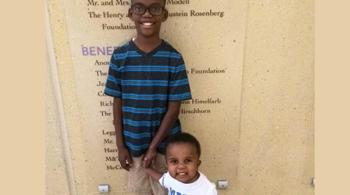

By the time she was in second grade, Jane Lockwood was already being teased by her classmates who didn’t understand why the young girl was allowed to sit out during P.E. classes while everyone else had to run. And they certainly didn’t approve.

By the time she was in second grade, Jane Lockwood was already being teased by her classmates who didn’t understand why the young girl was allowed to sit out during P.E. classes while everyone else had to run. And they certainly didn’t approve.

So, with her mom’s help, she sat down and wrote a letter. Then she read it aloud to her classmates: “I have muscular dystrophy,” she explained. And so, if she didn’t participate in physical education or other strenuous activities, it wasn’t because she didn’t want to or because she was the teacher’s pet. It was because she couldn’t. After that, her classmates gave it a rest. Now 14 years old, Jane remains as active as she can and loves the same things most teenage girls do. But her disease is progressive, and there are few treatment options, says her physician, Kathryn Wagner, director of the Center for Genetic Muscle Disorders at Kennedy Krieger Institute.

That’s something Wagner hopes to change.

Under normal circumstances, muscle has a tremendous capacity to recover from the natural wear and tear caused by exertion—not so for patients with muscular dystrophy. Muscle breaks down more easily and does not fully regenerate, eventually causing increased weakness over time. Unlike many of the dozens of forms of muscular dystrophy, there are no clinical trials for the rare type Jane is diagnosed with: limb-girdle muscular dystrophy.

Wagner’s research about novel treatments could play a significant role in the future of patients like Jane—and it’s a prime example of the kind of translational research that drives patient care at Kennedy Krieger. “The work I do should be applicable to many different muscle diseases,” she explains. “It crosses the lines between specific diseases so that therapies being developed for one form of muscular dystrophy could feasibly be applied to another.”

One current clinical trial focuses on a drug that would preserve and regenerate muscle. When that trial concludes, the resulting treatment could hold promise for patients like Jane. If successful, Wagner believes that a pharmaceutical treatment could be made available within the next five years. In the meantime, Wagner works with Jane’s family to manage her disease and keep her strong, so that when that time comes, she’ll be primed and ready.

“We were so lucky to find Dr. Wagner. She and Jane had an instant rapport, and I knew from the beginning it was a perfect fit,” says Jane’s mother, who is also named Jane. “The combination of her clinical work and her research are essential. We love working with her.”